Master Class: Know Your First Amendment & Protesting Rights

Master Class: Know Your First Amendment & Protesting Rights

As an American citizen, you have the right to protest and speak freely against your government. Over the course of the summer of 2020, injustices at the hands of the police sparked outrage across the country, inspiring thousands to take to the streets in protest. Unfortunately, corruption authorities, false allegations, and inaccurate information have run wild, leading many innocent citizens to be unlawfully arrested, apprehended, dispersed, harassed, and even murdered. In light of these events, attorneys across the nation have been working to offer legal rights information to U.S. citizens — it's time to learn what your government can and cannot do under the First Amendment.

In a webinar recorded June 19th, 2020, Maddy Martin sat down with Valerie McConnell of Casetext and Justie Nicol of Nicol Gersch Law to discuss the rising tensions between the general public and the police and how common injustices can be interpreted in the eyes of the law. Together, they also address the importance of knowing your rights, the proper preparation steps you can take prior to, and in the midst of, an arrest, and how to find qualified attorneys and adequate legal representation if you're arrested.

To learn more about this discussion, we encourage you to read the full transcript of the video below, edited for readability. You can also watch the full webinar for free on YouTube by clicking the image below. To check out more videos like this one, with tons of free tips for and from lawyers, subscribe to our YouTube channel!

Moderator

Maddy Martin

Head of Growth and

Education at Smith.ai

Speakers

Justie Nicol

Criminal Defense Attorney at

Valerie McConnell

Director of Support at

INTRODUCTION:

MADDY MARTIN, HEAD OF GROWTH & EDUCATION AT SMITH.AI:

Okay. Awesome. Cool. So I am going to monitor for anyone who starts. We’ll wait just a minute and see if anyone joins in, and we are recording.

Okay. Welcome everyone as you’re coming in. We will get started in just a moment. Nice to see everyone here. I hope everyone’s having a good Friday so far.

It is blazing hot here in Buffalo, and we don’t really like AC, so I’ll try not to pass it. How’s the weather in Colorado, Justie?

JUSTIE NICOL, NICOL GERSCH LAW:

It was actually rainy yesterday. So it’s about 60 degrees right now. Maybe a little bit warmer 62.

So my dogs are inside instead of outside in the rain because they’re pampered. This one is like, “I must appear on camera at all times.” So he’s right here.

MADDY:

No, no, it seems just they’re convenient company. Does he queue up your notes up for you?

JUSTIE:

Yeah. Yeah. He likes to make appearances in our morning team meetings, too. It’s better.

You have that or the horse. I mean, you know me. I’ll put the horse on camera, too.

MADDY:

Maybe you’ll do a Zoom from horseback one time.

JUSTIE:

I haven’t taught one yet. I have done plenty of Zoom conferences from horseback.

MADDY:

You’re right. Exactly. You can have, maybe your GoPro or something. One of those selfie sticks, right?

Okay. So, we will get started.

Awesome. Everyone, thank you for being here. We are so happy to invite you to join us today for a discussion on protester rights, first amendment rights, how that’s currently playing out today and with a historical perspective.

So we’ve got Valerie McConnell here from Casetext, which is legal research software powered by AI, and Justie Nicole from Nicol Gersch Law in Colorado, a criminal defense and animal rights attorney.

Did I get that right, guys? Can you introduce yourself, please?

JUSTIE:

Yeah, go for it. Valerie. I’ll let you start first.

VALERIE MCCONNELL, DIRECTOR OF SUPPORT AT CASETEXT:

As Maddie said, my name’s Valerie. I’m an attorney and the director of support at Casetext. We are an AI-based legal research platform. And I will be sharing a little bit today about cases that will hopefully provide a good jumping-off point if you want to research these first amendment issues further.

But the real-world perspective is going to come from Justie.

JUSTIE:

Hi. So I’m Justie Nicol. I am a criminal defense attorney in Colorado. We are about to launch into family law, which has nothing to do with protests.

But I am a managing partner and doing a lot of protest rights litigation right now. We actually have signed a couple of new cases, took a few pro bono cases because of the protest here as well.

So this is my daily life at this point. We have a number of other cases where police have operated questionably. I think I just got my last one dismissed. I think I have maybe one more in Boulder that I’m still working to dismiss.

But the real-life stuff, I’m in the trenches every day.

MADDY:

Wonderful. Well, I will just before we get started, introduce myself, and there will be a – for anyone who is asking – a replay available so we are recording this.

I’m Maddy Martin, the head of growth and education for Smith.ai. We are a virtual receptionist service for attorneys and many other professionals. Justie is included in our clients.

And I’m happy to, often, co-present with her and join in educational seminars like this. So I’m very happy to have our friends here today and Casetext partners with Smith.ai as well.

If you do need help, know that we are not only available for 24/7 receptionist and chat services. We are also as part of this greater initiative supporting attorneys who are serving those needs of protestors.

And we are offering free call answering and chat answering during this time. So, I will post the link to the document with more information on that. You can get in touch with us if we can be of service to you.

So, without further ado, Valerie. It would be wonderful if you could set the stage here and share what is in common parlance. Your first amendment rights, and how does that relate to the discussion today around protests or rights?

VALERIE:

Sure, absolutely. So I’m going to share my screen now. Hopefully, everyone can see this, okay.

So I’m going to discuss a few key cases that pertain to the right to protest under the first amendment—discussed in cases that you can maybe use for further research.

And I’m going to pause between each discussion of these cases to ask the real-world perspective from Justie because she’s the one in the trenches, and I’m just hiding here in legal research.

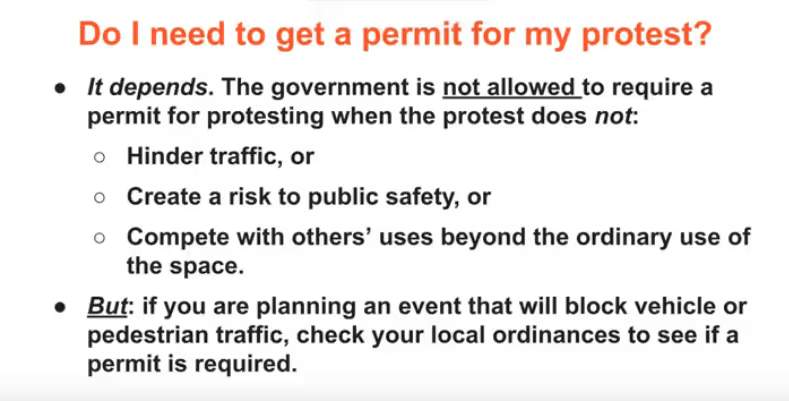

So, the first set of cases that I want to discuss, I think actually are a bit interesting, but it concerns whether you need a permit for protest.

PERMITS FOR PROTESTING

Now, interestingly, I think when people want to protest, they’re not usually thinking about getting a permit. Right?

They’re usually pretty caught in the moment. They want to go out there and make their voices heard, but a permit is sometimes required, as shown here on this slide.

Whether you need a permit can really depend on where, when, and how you want to protest.

Now what the government cannot do is require a permit for protesting when the protest does not hinder traffic or create a risk to the public or compete with others’ use of public property beyond the ordinary uses of the space.

So if you’re planning an event that will block vehicle or pedestrian traffic. It is advised to check your local ordinances to see if a permit is required.

PROTEST PERMITS: KEY CASES

But, the cases that frame this discussion. I put a few of them up here.

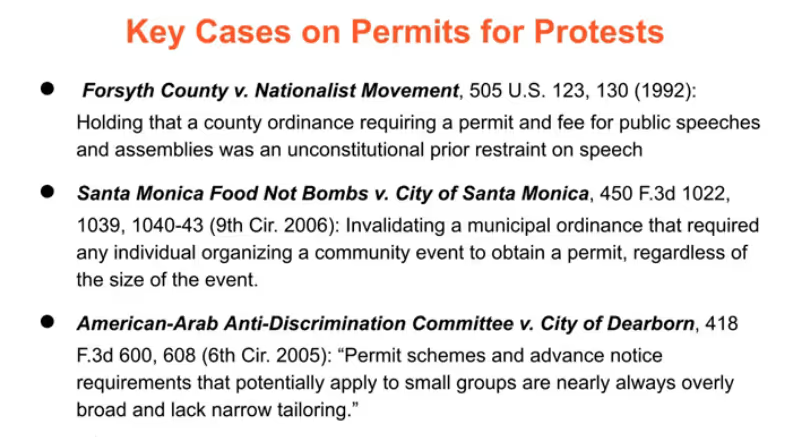

The first case on my list is a case from the US Supreme court, Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement. And that case, the US Supreme court struck down an ordinance that required a permit and a fee for public speeches and assemblies.

And this particular ordinance was problematic in that it required a lot of government oversight and discretion. People had to get approval from the County and pay fees before protesting or assembling.

That amount of government involvement and discretion to say who could protest, it was found to be an unconstitutional prior, straight on free speech.

Another case that discusses the right to protests, and permits, in particular, is the case of Santa Monica Food Not Bombs v City of Santa Monica. This is a ninth circuit case, which invalidated a city ordinance that required any individual that was promoting an event to obtain a permit.

And this was just a blanket rule applied. Regardless of the size of the event, you had to get a permit before organizing anything in public. Here again, the problem was that the ordinance was not narrowly tailored. It was super broad.

Now, in this case, the ninth circuit did recognize that a city could require advanced notice and some coordination for really large events that would present traffic and other issues.

But here, this ordinance just was too broad because it applied to literally any public gathering.

And this proposition, that the government cannot impose these broad permitting requirements on anyone who wants to have a public event. It was reiterated in the case of American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee v City of Dearborn, a case from the sixth circuit.

And I put up the pertinent quote here. The sixth circuit said, “Permit schemes and advanced notice requirements that potentially apply to small groups are nearly, always overly broad and lack narrow tailoring.”

The takeaway from these cases is that permitting requirements have to be narrowly tailored in order to be valid. There needs to be some legitimate government interest in public safety and the need for coordination to require a permit.

A city can’t just require a permit for any public gathering anywhere, regardless of the size. And a city can’t impose a permitting system that requires a lot of government discretion because then the government essentially gets to say, “Who can protest what?” Which is unconstitutional.

Okay. I want to pause now and talk to Justie, who has actually dealt with this.

So one question I was thinking, as I’ve been reading these cases. Let’s say you are in a protest, and the protest is not blocking traffic. An officer comes up to you and says, “You need a permit to protest here.”

Any advice for what a person should do in a situation like that?

JUSTIE:

I think the first thing is determining where you’re actually standing.

So if you are standing in a place that blocks access to critical government buildings, even if it’s a public forum, you might be asked to lawfully move. Other than that, there’s distinctions between protesting on a sidewalk, that’s a public place, or protesting in the middle of the street.

We have some of these clips that are on Twitter, and everything was. Even here in Denver, Denver PD has literally ran over a protestor and fired pepper and verbal. It’s pepper spray and rubber bullets at protestors early on in the protest for being in the street.

There’s been no mention, from what I’ve seen, of a permit being required or requested because most of the protests here in Denver, at least, and most that I’ve seen nationwide, are really happening in public spaces right now.

Some of it is hard to control on a municipal level because there are wide-open public spaces here.

Universities and other places have designated free speech zones, where permits for additional protests outside of those areas may be required. But really, right now, what we’re seeing is less about you need a permit to be here and more you’re blocking traffic, you’re blocking access.

This is out of control and then curfew violations, which are completely separate.

What we see a lot is in the middle of the day, the permit has been obtained for a march, which is on the streets. I know a number of organizers who have done that, including attorneys against police violence here in Colorado.

They’ve actually pulled permits and shut down certain areas of traffic in order to safely march through the area.

But what happens after that is they reach their end zone, which is usually around the Capitol here in Denver. And then, of course, City Center Park.

And then it just blows up from there. People don’t disperse at the end of the event. More people are coming. It’s growing in size.

Then people are violating curfew, and that’s after-hours when we were seeing rioting and property destruction as well.

So, it’s hard when you are the person or the group that is pulling a permit. And then you’re done with your allotted time, but you’re out of your attendees are out of your control. If you’re pulling a permit to block traffic, that’s one thing.

You’ve done everything you can lawfully to organize your right to protest.

And when it morphs into something else is when you have to worry about additional liability too.

So I’ve had other attorneys and other states, Minnesota included, they reached out to me to also ask about sound amplification because that’s something that does require permits in a lot of places.

So if you’ve got loudspeakers on your car in order to corral people or broadcast your message, usually that’s fine, but that’s something because it can violate noise ordinances that the city can crack down on as well.

So sound amplification is something you might have to pull a permit in advance. I literally was like troubleshooting with a Minnesota attorney. She’s like, what’s the worst thing that can happen besides the sound applicant, amplification materials, and equipment being destroyed.

And I’m like, "Well, A.) they should get new insurance or better insurance or up their insurance. B) don’t put who owns it on it." Right?

If you don’t want to be burdened with it, don’t put, who owns it, just lend it to the group. That’s fine.

Make sure the group gets a permit or is aware of the permitting requirements before they broadcast and that sort of stuff.

So some of it is practical stuff. Some of it is permitting stuff. And COVID throws a wrench in everything. You’re not even supposed to be outside.

MADDY:

Yeah. Endangering. Yeah.

And your responsibility personally for taking care of your community and others who are coming in contact with you. And what role would that play?

Like just to jump in here for a second, Justie, like, there are some urban areas that have a lot of residential space. So, if someone has a private home and they’re sort of near downtown or even apartment buildings and things like that, what role is there for that private property to host these protests?

That sort of feels like it’s in a public space, but it isn’t actually. Is that some noise space that the community considered affected?

PROTESTS ON PRIVATE PROPERTY

JUSTIE:

So private property, just like the new slide here indicates, it’s entirely up to the property owner.

What goes on, on their property as long as they don’t interfere with other properties.

So, I actually own a building in Fort Collins, which is right next to the Planned Parenthood. And we have had a number of protests for years and years at Planned Parenthood. And as I say we – the community has protested at Planned Parenthood in various forms.

And as soon as it spills onto my property, they’re very, very close to a driveway and a drive aisle. We have had to forcefully remove protesters from our property because it’s private property and you’re blocking traffic.

And if you get hit by a car in my parking lot, even though you’re protesting at my neighbors, I’m somehow still liable for the property damage like a slip and fall, anything like that, if you fall on my property, were injured on my property, and if you’re not lawfully present there, I can kick you off.

So I restricted private property protests in that instance, but on the other end of things, I could also allow it. It’s entirely up to me as long as my neighbors are not detrimentally affected, like in that case with car and pedestrian traffic.

Signage, you can put whatever signs what you want up on your own property.

You pretty much set the rules for your own property.

MADDY:

Okay.

And that’s, but it’s mostly with respect to the physical presence directly on the property and not like the noise generated around the property?

NOISE ORDINANCE COMPLAINTS

JUSTIE:

You still have the noise ordinance complaints that are possible, just like you would with house parties when you’re an undergrad. The cops get called because there’s 50 kids that are tailgating before a football game. So you’ve got to be concerned about that.

But if you’re being respectful, you’re not using profane speech or sound amplification. So broadcast unnecessarily, you should be fine.

The best tip I have is just to talk to your neighbors. Talk to your neighbors in advance.

MADDY:

Be proactive. Let them know in advance.

JUSTIE:

Yeah. Yeah. Let them know you’re hosting something.

And some of it is large commercial property owners could have a stake in this as well, where our properties are in Fort Collins. We’re right across the street from CSU. We have a large student contingency.

We could open up our parking lots to protestors, just about any time we would like to, as long as we don’t infringe on our neighboring businesses.

MADDY:

Got it. Valerie, sorry, back to you.

VALERIE:

No, not at all. This is the purpose here to have a discussion around the slides. I don't want to drag people through some old Supreme Court cases.

And the reference to COVID made me realize that, these cases, though useful, don’t capture all the things that are going on right now. We probably have some very interesting cases dealing with COVID, protesting, and all that entails from a liability perspective.

JUSTIE:

Yeah. I saw something on Facebook the other day, which was, they’ve canceled our 4th of July parade. But they’re allowing the protest to go on.

And I’m like, "Wait a minute, wait. This isn’t different from historical case perspective. There’s a government actor involved in one of these things. And then there’s the constitutional right to protest and freedom of assembly in the other." So the government doesn’t have to host a parade for you on the 4th of July during COVID. That’s just not going to happen, but they also aren’t really enforcing stay-at-home orders nationwide anymore.

I think most places are starting to lift those.

So the biggest concern you have with the protests and violating your first amendment rights are whether your first amendment rights will trump a curfew order and trump a stay at home order.

So that’s going to be some interesting case law I think we’ll see, come out of this, too, is somebody who’s been charged with violating stay-at-home orders—or violating administrative orders for the protection of the public during COVID versus their first amendment rights.

And I’m pretty certain your first amendment rights are going to trump an administrative order to stay home during COVID.

But we’ll see what the Supreme court says in probably, like, three to five years.

VALERIE:

Right.

Although, actually, Justie, you raised an interesting point, which is not on these slides because the old cases don’t deal with the situation you mentioned.

You mentioned curfew orders. How does violating a curfew order, how does that impact a person’s right to protest? Or how did the curfew orders impact the right to protest?

Because actually, that’s something that I haven’t seen much in the case law, which, as you pointed out, is going to be a big issue now.

JUSTIE:

Yeah, I haven’t seen a whole lot of really authoritative cases on it.

The problem is most curfews are set at the municipal level. And so the violation for a curfew is usually just a muni fine here in Denver, anyway. It may or may not go on your background check.

It’s not necessarily like an arrest. I mean, it’s probably an arrest, but it’s not necessarily booked and reported to the national databases for purposes of a background check if it’s only going to be a muni.

But the problem that you have is you’re seeing mass numbers of people arrested for curfew violations, really, not booked everywhere and released the next morning, if not sooner. And I think, gosh, LA or one of the major Metro areas, their district attorney actually said, and I think it might’ve been Denver, too, they said, "We’re not prosecuting curfew violations."

So they just dismissed, I think, 320 cases or something ridiculous like that here, where it was like, but these people had to spend a night in jail anyway. Right?

You choose not to prosecuted — that’s great, but there’s a disconnect between your DA and law enforcement officers who are using this as a method to clear the streets.

Curfews are a little bit hard, right? There’s not a Supreme Court case directly on point that I know of. Maybe there is.

VALERIE:

I don’t know one either.

JUSTIE:

But there are some things, in general, that the police have to do.

If there’s a clear and present danger of a riot or interference with traffic or other immediate threat to public safety, they can issue a dispersal order, which is maybe a little bit different than a broad curfew.

But they have to give people a reasonable opportunity to comply. They have to give clear and detailed notice of the dispersal order. And they have to provide a clear exit route to follow.

So what I’m seeing on a national level is that those things really aren’t being done. And I don’t know what the liability to the police force is for that.

But in terms of your rights to assembly, they only go to the clear and present danger to public safety line.

Once that line is crossed, kind of all bets are off a little bit. But yeah, the notice of the dispersal order, the opportunity to comply in an exit route.

There’s not like a map out there that they’re giving that for free. I mean, maybe they should push through an Amber alert to everyone’s Apple watches and say, “Hey, exit route is here.”

They’re not. They’re not taking advantage of technology or doing that sort of stuff. It’s just an easy way to arrest a lot of people at this point.

MADDY:

One question as we talk through the rights of different individuals, one thing that comes to mind is minors and the role of maybe employers in permitting, and some of these conversations probably happening in the workplace.

So maybe the first one we can tackle is parents who bring their children to protests.

What risks may they bring about or experience and how to mitigate those? And maybe, minors who are protesting; maybe they’re 16, 17, or something, certain precautions that they may need to take.

MINORS ATTENDING PROTESTS

JUSTIE:

So the hardest thing about, and we’ve seen just as in 1964, the Civil Rights Act and the protest that led up to that, there were a lot of young people who were activists in that sense.

We’ve seen one protestor here made the news. He was 15, the first night of protests here in Denver.

And you’re a freshman in high school, maybe eighth grade. It’s a very different dynamic with police when you’re that young. Juvenile prosecution can happen in Colorado, at least. If you are ten years older, so you are subject to arrest just as an adult would be.

Now, the hard part is, if your kids are there and you’re a respondent’s parents, you are also required to be in court. If they are arrested in Colorado, every juvenile gets an attorney free of charge if their parents cannot afford one or refuse to provide one.

I don’t know whether that’s the case in every state. I would wager it was not because that was a recent law passed here.

So, kids have juveniles, and children have a different issue. And then there’s always the issue of potential harm to them.

I don’t think I’ve seen any child abuse charges for parents exposing their kids to risk in this sense yet. That’s not to say it’s not coming.

MADDY:

How much violence there’s been, I think not just also the older kids, but maybe also parents who are bringing strollers to protest.

Is that advisable, or is there a way to find other childcare, especially if they’re so young as to not even remember?

If the parents are looking to expose the children for an education or experiential sort of thing, do they want to bring that in as a cultural value?

This is something that we do as a family, perhaps, but as a baby. What would be the benefit of bringing a baby to something like that?

JUSTIE:

And as a mother of a toddler, I get it, right? We’ve done the women’s march, a couple of different things, but at the same time, you have to be cognizant of if there’s a risk to your child, you have to leave.

You have an obligation before anything to that kid because there are reckless endangerment laws in Colorado.

There’s also knowingly or recklessly exposing your child to the risk of physical harm. That is child abuse, and it’s a misdemeanor in Colorado. I haven’t seen that charge in this context yet. We’re pretty, in Colorado at least, we’re pretty safe during the day.

Most of our events have been permitted and peaceful and that sort of thing. The marches have been very well organized. It’s the evening and that transition to getting close to that 5:00 PM curfew where people are trying to get out, and other people are coming in, the troublemakers are coming in.

There’s always going to be that. We had a scare in Greeley. I think they shut down the courthouse on a Friday because they’d heard that Antifa, whatever, was coming to the courthouse and a bunch of rural counties were thinking that they were going to have violence and everything.

And I’m not here to comment one way or the other on whether that’s a terrorist group or not. But I think as the day wears on, people get tired and tempers–

MADDY:

Drinking alcohol.

JUSTIE:

Alcohol’s involved. There are public consumption of alcohol and drugs in Colorado. Marijuana is legal.

Although marijuana, generally speaking, is not going to be a big insider for violence. But we have had a number of businesses who have been raided, alluded that sort of thing on Colfax, especially, which is right next to where the capital.

MADDY:

So, Valerie, I don’t think we’ve touched on this slide yet. Maybe we go to just go back in anything we didn’t cover around public versus private.

VALERIE:

Yeah, absolutely.

So Justie highlighted the distinction between protesting on private property versus public so I’m going to go for you a couple of cases that really discuss that distinction. And then we’ll turn to her for a few more questions.

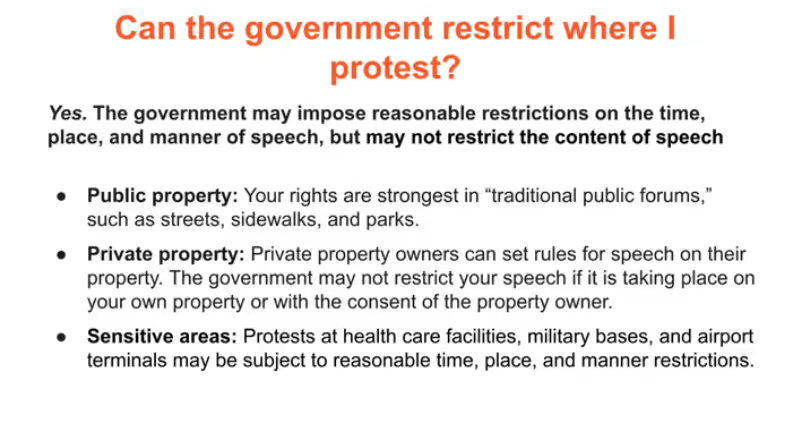

So on this slide, I summarize the three basic categories that you’d see in the case law pertaining to why your protests location matters.

There’s public property, which historically, is considered that the public forum, where your right to protest is most protected under the first amendment. Then, as Justie said, you have private property where the private property owner really gets to say whether somebody can protest there or not.

And as Justie pointed out, you could put up whatever sign you want on your own private property.

You have to be careful of noise ordinances and things of that nature. You can stand on your own private property and say whatever you’d like.

And then there are areas that are called sensitive areas for lack of a better term, but you’ll find these areas, in front of health care clinics or abortion clinics, military bases, airport terminals where the government imposes some reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions.

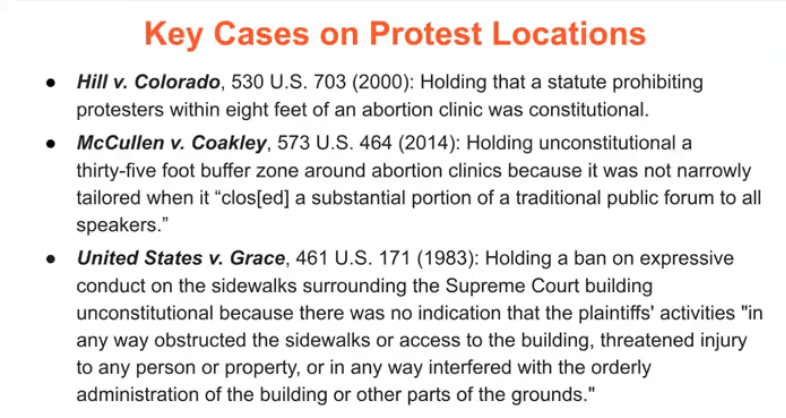

So a few cases that discuss these distinctions between protesting on private versus public property in some depth are the cases that I’ve put up here.

So the Hill v. Colorado case, a US Supreme Court case in 2000. Struck down, or excuse me, upheld a statute that prohibited protesters from getting within eight feet evitable as an abortion clinic.

There were grounds for restricting protests that close to the abortion clinic because it was blocking traffic. It was interfering with patients’ right to access the clinic. So it was okay to have an ordinance prohibiting protests that was making that close.

On the other side, we have at another US Supreme Court case from 2014. That said a 35-foot buffer around a clinic with no protests could be held in a 35-foot radius. That was too broad.

So you couldn’t prohibit all protests within 35 feet of an abortion clinic. That was not narrowly tailored, and it wasn’t related to the interest in making sure that people could access the clinic.

And that seemed to impinge also on the traditional public forum, which is sidewalks, somewhere between eight and 35 feet is the sweet spot, I guess, if you want to protest by a healthcare clinic.

And an old case, but a good one, United States v Grace from 1983, upheld the right to protest on sidewalks surrounding the Supreme Court building as being the ideal example of the public forum. It’s protesting on the sidewalk Supreme Court, which people are allowed to do and can do.

This is continuing to consider it to be your pinnacle first amendment right to protest right outside the courthouse.

So these cases outlined some guideposts. As you can see with the Hill and McCullen cases, it can get very specific, especially when you’re dealing with these sensitive areas like healthcare clinics.

One question that I want to ask Justie, if you are protesting in an unauthorized location, private property, or even one of these sensitive areas like in front of a healthcare clinic.

What are some of the criminal charges that one can face for protesting in a location where you can’t protest?

POTENTIAL CHARGES FOR PROTESTING IN UNAUTHORIZED LOCATIONS

JUSTIE:

I think you’re mostly looking at municipal violations, once again.

But sometimes, you will have things, especially in the Hill V Colorado case. I’m pretty sure I remember that one. I think that’s why when we’re next door to Planned Parenthood, we get people because we’re the neighbor that’s more than eight feet away.

Yeah. I think what you’ll end up with is, you’ll have harassment charges coming. Maybe some disorderly conduct, unreasonable noise, or fighting in public. It is an offense to spit on someone.

So, especially right now, with COVID, it can be a very high-level misdemeanor. And if you’re spitting on a cop or an EMT, it can always be a felony as well, especially if there’s an intent to infect.

So when you have these protests that are going on, and people don’t have their masks on, and spitting has become kind of this, I think, counter-protest maybe I don’t even know what the right word is, those are criminal acts.

We saw an attorney recently, and I can’t remember where she was. She was charged twice with spitting on someone who was protesting, and it was a white female attorney.

And I’m, like, at that point, you have to report that to the bar as well as ethics council, getting everyone involved in that.

So it can be a felony. You can run the gamut and what charges you actually end up with if you’re just present within eight feet.

Most likely, you’ll have multiple opportunities before they will arrest you or charge you with anything.

They will warn you to get back or warn you, warn you, warn you. But if you’re getting up in someone’s face, they may detain you. They may look at disorderly conduct. They may look at obstruction charges for disobeying a lawful order.

If there are police there and you refuse to disperse, of course, if you ever resist arrest, you will always have resisting arrest charges as well.

So there’s a wide variety of criminal conduct that goes along with this kind of stuff.

And, whether or not it’s appropriate to charge somebody under these circumstances is definitely something different.

Right now, we’re seeing a lot of pushback, of course, with resisting arrest, especially with freedom of the press and legal observers, also being arrested at some of these protests.

MADDY:

So, Justie, that brings up a really good point with resisting arrest.

And we see a lot of videos where people are very upset and raged, that they feel there’s unfair treatment happening, and they are resistant.

Where is the definition of resisting arrest? And how can you, I mean, plead your case, so to speak in the moment? Do you just never try and resist? What is the sort of best practice there and practical?

RESISTING ARREST

JUSTIE:

The best practice is just not to physically resist.

If the cops are going to arrest you, they’re going to arrest you. If you resist, you actually can cause new charges.

So we have had cases where somebody was under arrest for suspicion of something else. Right.

And then once they finally put handcuffs on you and try to take you to jail, when you’re resisting arrest, resisting being handcuffed, that starts a whole new case.

So I can get, as a criminal defense attorney, I have gotten the underlying charges dismissed, but resisting arrest is a new crime, and it starts all over.

So the best bet is if they’re going to arrest you, they’re going to arrest you and no matter what you do, it’ll only make things worse to resist.

There are lots of people who will tell me, but resisting arrest, resisting on unlawful arrest is not resisting arrest.

MADDY:

Right?

JUSTIE:

There’s very little distinction. Yeah.

MADDY:

And that’s really where you need an attorney, maybe.

JUSTIE:

Yeah. And that’s where you need an attorney. Yeah.

And it is just splitting hairs and if you resist arrest, you’re going to end up in a world of hurt because they, at that point, can use force on you lawfully so.

MADDY:

And you really put yourself at risk, not just for the potential charges going through, but actually for physical harm or worse.

JUSTIE:

Exactly. Okay. Yeah.

And in terms of filing a 1983 claim and getting rid of qualified immunity and trying to sue the cops, if you’re resisting arrest, you can’t sue them for the underlying stuff.

They’re going to end up charging you with not just curfew violation, but also resisting arrest. And they may have had dead to rights on resisting arrest, because there’s 15 people, it’s on video.

MADDY:

Right. And all the cameras that are around, absolutely, you have to be pretty sure.

JUSTIE:

Take a plea or are convicted on any of the charges, not just the underlying one, you often cannot have a civil suit against the police successfully at the end.

So, we’re trying to get full on dismissals of some of this stuff in order to be able to go after the police for obsessive excessive force or unlawful arrest or excessive prosecution even. If you take any criminal conviction, even if the plea deal was offered and you’re doing it to stay out of jail, you cannot sue the cops, generally speaking.

So it’s very, very hard, under those circumstances. The best bet is to just be like, “Okay, arrest me. I will see you in court.”

MADDY:

Right, right. The least potential for damage, whether short-term or long-term on that.

And really, it sounds like you’re saying, don’t even begin to argue, even verbally. And maybe, if you know that you are someone who is hot-tempered or prone to argument, you stay more on the back lines and not in the front lines, where you’re more visible to the police.

JUSTIE:

Yeah. The red-headed fiery tempers among us.

MADDY:

Is there anything else that you wanted to add here, Valerie?

VALERIE:

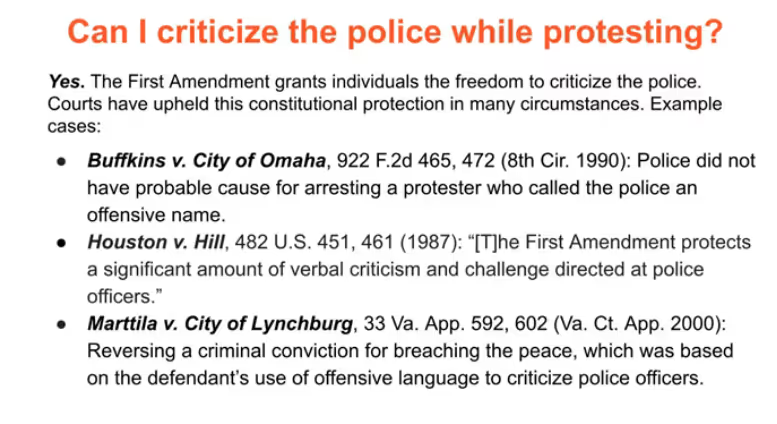

Actually, your discussion here about interacting with the police sets up the next slide really well, where I collected a few cases on criticizing the police.

CRITICIZING THE POLICE WHILE PROTESTING

The three cases I put up here, I’m not going to repeat what the protestors said to the police. It’s some pretty, profane language, but since you’re talking about interacting with the police. I can go through these cases briefly.

And then I actually want to ask for Justie’s perspective on some of these issues.

So the three cases of the court make clear that the first amendment does protect your right to criticize the police. And there are a number of cases upholding this. The few I’ve put up here are particularly colorful examples of that.

So the Buffkins v. City of Omaha case, an eighth circuit case from 1990. I just put a brief summary. I encourage everyone to look up and read the entire case. But the police did not have probable cause for arresting the protestor, who called the police and offensive name, I will repeat that here, but it was during a protest.

The police interact with the protesters. The protesters called the police a number of offensive names and were criminally charged and were arrested. And I think they were charged with disorderly conduct.

But essentially, the only conduct has issue was that the protestors were calling the police names. And that was not actually probable cause for arresting a protest or under those circumstances.

The next case I put up here, the Houston v. Hill case, a US Supreme Court case from 1987. This case makes clear that the first amendment protects a significant amount of verbal criticism and challenged directives by police officers; note, however, verbal.

So, you can take to the streets and say things about the police. But, this protects verbal protests. Obviously, physical interactions with the police are not covered by this rule.

And in the final case I put up here is actually a case from Virginia, a State Court case, where the court reversed a criminal conviction that was based on breaching the peace and the conviction for breaching the peace was simply based again on a protestor using offensive language against police officers.

So the takeaway from this, the case here is that simply saying bad things about the police in public, even calling the police offensive names, is not grounds for arresting them. It’s not a crime. It’s protected by the first amendment.

Now having made these academic points, I want to get Justie’s perspective about interacting with the police.

So, if a police officer comes up to you in a protest and starts talking to you, what happens in these cases?

The police officer or the protestors spoke back and said some pretty horrible things. If a police officer approaches you during a protest, are you obligated to speak with them?

JUSTIE:

No, not ever.

You don’t have any obligation to talk with them at all.

If they refuse to leave you alone, the best thing you can do is just remove yourself from that situation. Go to the back lines or protest in a different area. There’s no obligation to talk with the police.

There’s no obligation to engage in any sort of debate with them at all.

The big thing that we see is, they’re at the point of arresting someone, right?

Someone will automatically blurt out, "What am I being arrested for?" You have the absolute right to ask that question.

And in fact, I would suggest that you do that. First off, ask, always ask, if you are free to leave. If they say you are free to leave, leave.

Right then, don’t stay, don’t talk anymore. If they touch you or put hands on you, ask why they are doing that, and ask if you are free to leave?

I mean, it is literally, “Am I free to leave? Am I free to leave? Am I free to leave?" Every single time, like you get there. If they order you to sit down on the curb, and you’re, “Am I being arrested?” Don’t even ask if I am being arrested.

“Am I free to leave?” Those are the words you need to remember.

If you are under arrest, you absolutely do have the right to ask why you are under arrest.

If they tell you, great, but cops can lie to you. They have no obligation to tell you the truth. So if they’re going to try and get you to flip on somebody else or snitch on somebody, they can persuade you however they would like.

So they may tell you you’re under arrest for something, and they may tell you you’re under arrest for something that is not what you’re under arrest for. And so later, the district attorney actually makes most charging decisions.

So DA’s can add charges up until the day of trial and amend charges as well.

So, what you’re arrested for doesn’t end up necessarily being what you are charged with when you go to court.

Sometimes within 72 hours, they have to make that change later. They will make, in some other cases, they will make it later. But the three things to remember is ask if you are free to leave, if you’re under arrest, ask why you were being arrested.

And then, if you are under arrest, asked to speak to an attorney, that is it.

Those are the three things: “Am I free to leave? Why am I being arrested? I want an attorney.”

And not, I might want an attorney, or should I have an attorney? I want an attorney; unequivocal because if you are questioning whether you need an attorney, they are still free to talk with you.

But those three things should help you get through any sort of interaction with the police.

VALERIE:

That’s, I feel like, that’s kind of great advice that the defendants in these cases could have used. It happened during those.

I think the gray area where the police were coming up with them, it wasn’t clear they’re under arrest, and they started debating using some choice language.

JUSTIE:

But we see too a lot is, right now, in the era of cell phones, right.

In 1987 and 1990, not everybody had a camera in their pocket. Now you have cameras in everyone’s hands. And what you’ll see is somebody’s getting arrested and their buddies over here taping the whole thing.

The problem becomes when the buddy gets too close and the police aren’t sure with what that out of the corner of their eye what he has in his hand or what she has in her hand, is it a gun? Is it a weapon? Is it a stick? Is it a cell phone?

So they will turn on the observer and then arrest them. So there’s a whole line of cases about, “You do have the right to videotape the police.”

You absolutely can stay and observe someone else being arrested. You can not have your cell phones searched without your consent or a warrant.

Now, if your phone doesn’t have a password on it, it’s a little easier to search for those things. So put a password on your phone or put facial recognition on your phone if you have to, but a password is better than facial recognition.

The police cannot search your phone without your consent, cannot search your body without your consent, cannot search your bag without your consent.

The exception to that is, if you are arrested, they can search through you and your bag. They still cannot unlock your phone without a warrant, though.

MADDY:

So you’re not required to give your phone password or anything like that?

JUSTIE:

Never. Nope.

They can go and get a search warrant later. And I’m still, I’ve got a case right now with a juvenile where I’m like, good luck. It’ll take you a little while to get that search warrant on a stupid harassment case, right?

Like it’s the lowest class of misdemeanor we have. By the time you have the search warrant done, we will have pled this case and dealt with it, and he will have this off his record.

So those are my suggestions with regards to cell phones specifically.

Just maybe if you are going to videotape somebody, just say, “This is a phone, I’m taping this.” Don’t ask for permission.

The cops don’t need to give you permission, but let them know you are just videotaping. And then they’re less likely to think that you have a gun in your hand when you walk up beside them and hold it in their face.

Stay a reasonable distance away as well.

VALERIE:

That is good advice.

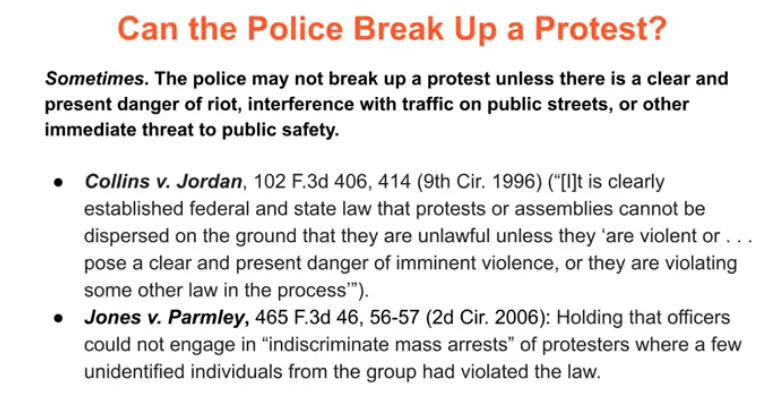

DISPERSING A PROTEST

So the last slide that I have prepared circles back to something that you mentioned earlier about dispersing a protest and when the police can do that.

So what I found in the case law, to date, which does not include obviously all the recent stuff going on now and all the unique circumstances presented today.

But the short answer, from the case law to date, is the police can sometimes break up a protest.

Justie, you mentioned this, but the police can’t break up a protest unless there is a clear and present danger or danger of a riot, or interference with traffic on public streets, or some immediate threats to public safety.

So the two cases that I’ve selected that illustrate this principle and some depth columns would be Jordan. This is a case from the ninth circuit, and it basically just reiterate the principle that is clearly established federal and state law that protests or somebody who cannot be dispersed on the ground that they’re unlawful.

Unless they are violent or pose a clear and present danger of imminent violence, or that they were violating some of their law processes.

The police can’t just come and tell you to disperse. There has to be that element of a clear and present danger.

And a case a bit more recent that I think really resonates today is that the Jones v. Parmley case from 2006 from the second circuit. I had my eye on that panel. But the second circuit net case held that officers could not engage in indiscriminate mass arrests of protesters.

So this was a situation where some people from the protest did things that were unlawful. There was a lawful protest and a few unidentified individuals in the group were rioting and looting, and violating the law.

So what happened with the police? The police came and arrested everyone they could find there.

So, Justie, now trained to today’s events. I think a similar fact pattern to the Jones v. Parmley case where you have a bunch of people lawfully protesting. And then you have a few unidentified people rioting or breaking glass in a store, and then the police tried to arrest everybody.

What have you seen in terms of the fallout from that? It might be too soon to tell but in terms of people who have been arrested simply for being there.

JUSTIE:

Yeah, what I mean, it’s a little bit too soon for us.

I think because of COVID, more than anything, every jurisdiction in this state, except for one, has jury trials and in-person appearances pretty much on hold until August 3rd. So they just bounced us another month, which means that most of these people who’ve been arrested for the protests may not have even gone to court yet.

They would have a bond set as soon as they were arrested, they were able to bond out their court dates, not going to be until August or September.

Hell, I had one set in November on me earlier, without even notifying me. I’m like, "November? This is crazy!"

So I have a feeling there’s going to be a lot of dismissals on things.

The hard part is that second circuit. I don’t know if it would be persuasive here in Colorado, which is the 10th circuit. But I don’t know if there’s anything directly on point here.

State versus federal jurisdictions are a little bit different. But this should be exactly what we’re talking about. Right? People are just getting arrested for being present, and you’ve seen it time and time again on the videos, on Twitter, and on other pages.

And it’s just disheartening that there’s this blanket attempt to just quiet the masses, and that is unconstitutional. Whether or not you agree with it, it is unconstitutional. Right?

So, we haven’t seen the shakedown of what will happen. But in my opinion, some of the cases we’ve taken, and we’ve seen here, are indiscriminate mass arrests. People have done none of the rioting or looting. They’re just present and can’t remove themselves from the situation fast enough.

Now, we’ll see whether there’s in self-defense cases or I’m sorry, then on conspiracy cases, there’s a requirement that co-conspirators often have to take steps to thwart the conspiracy, to remove themselves and denounce the conspiracy.

I don’t know whether that’s going to be something that they’re going to require in this.

It’ll be an interesting area of law if you just stood there and did nothing while someone smashed a window. I don’t think that they can charge you under conspiracy theory. But I also don’t know. They might try.

And then there’s no requirement that you were actually the one who does it. Just not stopping it was maybe enough.

So we’ll have to see, and there’s always civil liability. Now you’re concerned about, too, in these situations, of course, if someone is arrested and multiple people are arrested, say for vandalism, you’re all jointly and severally liable for the damages. So that could be thousands of dollars in these cases.

And if they’re arresting three or four people who are like 15, 16, 17, there you go. You’ve got a juvenile who will very likely have $3,000 bill when they walk out of court without having to hire an attorney. Thankfully in juvenile, you get a free attorney.

MADDY:

But, so in that case, and I truly don’t know, would the parents assume some of the responsibility for that financial compensation?

JUSTIE:

Yeah. And if he doesn’t or she doesn’t pay, there’s always the possibility you will end up back in custody for failure to pay your restitution. And that’s getting less and less nowadays, but...

MADDY:

Okay. Yeah, the role also, and Valerie, I don’t know if you can speak to this as well.

For the obligation, let’s say that there has been a lot of talk on social media that two groups are coming together to exercise their first amendment rights. We are expecting a bit of a powder keg.

What is the obligation of the police to staff up and to protect citizens? And that scenario to anticipate with a reasonable size force, is there any sort of precedent there?

POLICE OBLIGATION TO PROTECT

JUSTIE:

I was just going to mention counter-protests. So I’m glad – did you have cases, Valerie?

VALERIE:

I actually did not have cases on this issue. That’s a very interesting point. So I, unfortunately, I can’t speak to that.

But it’s something I actually want to look at right after this call because that’s an interesting angle. Thinking from the perspective of protest for what are the police’s responsibility, then to keep the peace?

MADDY:

And maybe now, also that we have more information at our fingertips than we may have in the eighties and nineties and obviously before then, where there’s a bit more information that’s readily available and maybe even expressed by many people and not just one, that there is a powder keg that’s about to happen or being planned or all this sort of setup for that.

JUSTIE:

My understanding is that, obviously, both sides have free speech rights. Whatever your perspective is, you have the right to come and protest or counter-protest.

The police, in my experience, are pretty much just there to keep the peace so they can keep both groups separate. But they can’t order one group or the other to disperse without these requirements. Right?

If it gets to this point where there’s a clear, present danger of imminent violence, I would hazard a guess that the police are going to tell everybody to go home. It doesn’t matter what side of the protest you’re on. They’re going to treat protests and counter-protests equally.

And then, generally, though, they don’t require you. If you’re a counter-protesting or protesting to be completely out of earshot of each other or out of the visual range of each other, that’s the purpose of the encounter, to protest the right to be there and provide an alternate perspective.

Yeah. As long as you’re not confrontational and physically confrontational, you can be confrontational and say whatever the heck you want on the other side of the street.

That’s what we see most of the time is there’s one area designated for this protest. There’s one area designated for this protest, and as long as they don’t intermingle, you’re okay.

But the police, I think, are more that, they’re trying to be Switzerland. And it’s a little harder when the police have a stake in this kind of protest. Right?

MADDY:

Right. They’re not really exactly a neutral party there, in some people’s minds.

JUSTIE:

Yeah. Yeah.

And so it’s almost two counter-protests. You have a protest, you have the police, and then you have another counter-protest. And the police are taking some sides.

At least what we’ve seen in the media and the media may be biased as well.

So from my perspective, everybody has free speech rights. We have different views on how criminality should attach to your protest rights, for sure.

MADDY:

But also, I expect that if you’re going to something where there are murmurings of violence or confrontation that could be physical and people are saying some very inflammatory things that have in the past led to violence, you don’t expect that the police are going to staff up extra to protect you.

That’s not necessarily a requirement, and they wouldn’t necessarily be negligent.

JUSTIE:

Right.

Yeah, and it’s very, very hard to see the police, civil rights attorneys have a hard road ahead of them.

Although there are some laws that are changing, at least here in Colorado. We, our legislature, just passed groundbreaking legislation. And I haven’t even had a chance to read the final bill yet, that limits police immunity. It does away with a bunch of protections.

So, it’s a good move in the right direction, but as we see with a lot of politics, it’s always a pendulum. You’re going to have some states go real far one way and then maybe come back a little bit. But, we do see that as time progresses.

So I hope that the cases continue to shed light on the new era of protests and during COVID no less.

MADDY:

Valerie, I think you may have wanted to say something.

VALERIE:

Yeah, just real brief, to piggyback off a couple of things that Justie said.

So as I mentioned, I did not see case law addressing the interesting situation of dealing with the protest and a counter-protest. Well, that’s not an issue. I looked into something else I’ll follow up on, but a couple of things that she mentioned.

As she pointed out, the police are likely to tell both sides to disperse. And actually, under the case law, the government shouldn’t favor one side or the other because that’d be seen as endorsing one message.

So if they say these people can protest, these people can’t. They’re clearly picking sides, which is unconstitutional preference, necessarily monitoring that.

The second trend that I’ve seen in the case law, and to echo Justie’s point about how hard it is to sue the police, it’s very hard to hold the police, the government liable for something they did not do, for failure to act.

I mean, it’s hard to hold them liable, period, but it’s especially hard to say you guys should have done X, but you didn’t.

There’s a bunch of discretion given to the city and the police for how to allocate police resources. And it’s extremely hard to say that the police should have done something to stop the violence, but didn’t.

And you see this in child abuse cases where they tried to hold the city or the police liable for trying to stop something that unfortunately happened, and oftentimes that’s completely unsuccessful.

MADDY:

Yeah, maybe that also relates to Justie, who was saying about co-conspirators who may or may not have actually been co-conspirators.

They just were standing by, how do you hold them accountable or liable?

CONCLUSION

So, this is a fantastic discussion. I can’t believe we’re already out of time. Really, time flies.

And thank you all for joining us.

Valerie, can you share, obviously you did a lot of this research through Casetext. Can you share if others want to get access to research tools like this? How they can access that, or if there’s a free trial or anything?

VALERIE:

Yeah, absolutely.

So you can just visit us at casetext.com. It’s like the word case and text one word, and you can sign up for a 14-day free trial.

We are also offering a deal for people who, for attorneys who are providing pro bono representation in connection with any civil rights work. If you contact us at supportatcasetext.com, we’ll hook you up with free access.

We’re trying to make sure that attorneys are encouraged to go out there and provide pro bono representation in connection with either representing protestors or any civil rights adjacent work.

MADDY:

That’s fantastic. Thank you so much for sharing that.

And if we can join in those efforts and answer any calls that are coming into those firms or return calls for you. Please let us know you can contact us or visit our website at smith.ai or hello@smith.ai.

Everyone. Thank you for joining us.

Valerie, Justie, thank you so much for your expertise and your time. This was a really fantastic discussion, and we will share the recording.

And for anyone who missed those websites, that is casetext.com and Smith.ai.

Thanks all. Have a wonderful day. Thank you.

Questions? Contact Us.

Have any questions about Smith.ai's virtual receptionists services or anything else mentioned in this webinar? Call us at (650) 727-6484 or email us at support@smith.ai.

If you’d like to learn more about how Smith.ai’s virtual receptionists can help your business, sign up for a free consultation with our team or get started risk-free with our 30-day money-back guarantee!

To watch more webinars like this one, check out our YouTube channel or access articles, guest blog posts, and other resources on the Smith.ai blog.

Take the faster path to growth. Get Smith.ai today.

Key Areas to Explore

Your submission has been received!

.svg)